The Times recently had an article about someone who was found innocent of a rape and let free after 21 years in jail. The article talked about the difficulty of finding the evidence in his case. This was something I researched heavily. The following is an edited version of what appears in my book. It’s useful for learning how to find evidence.

The best advice I can give though, for people who are looking for evidence: be persistent and be creative. Many times I was told something was lost, and it was later found by simply looking everywhere. An example of creativity in the following text. It’s a little choppy because I took out whole sections here and there.

The NYPD Property Clerk Division

DNA or blood barrels at the Property Clerk Warehouse.

Two years after 14-year-old Christine was murdered, [one of the cases I wrote about], a 49 was sent to the Property Clerk Division, asking them not to destroy any evidence connected with the Christine Diefenbach case. The “49” comes from a now defunct form called a UF49, and it simply refers to inter-departmental memos on police letterhead. Evidence stored at the Property Clerk is destroyed after two years, except for evidence marked “homicide” on the fourth line down on the property clerk voucher. That’s what’s supposed to happen. The commanding officer at the 102 knew how things really worked, so he sent the 49 to make sure everything was saved. It didn’t help. In spite of his request, some of the evidence was destroyed. “They’re dicks and they needed the room,” one detective explained. A 1963 report found that the police personnel in the Property Clerk were not particularly qualified, untrained and didn’t consistently follow the few written procedures that existed. The cops that were there were there because they were on restricted or modified duty. Restricted means they’re sick or have been injured, modified means they’re disciplinary problems and they’re being punished. No guns, no shields, no patrol or enforcement. The rubber gun squad, they’re called. A former Property Clerk employee from the 70’s called it a “no show job.” People were on the payroll but they didn’t show up. “Those guys don’t care,” another detective said. “They couldn’t care less.”

Not so anymore. After a long history of bad management, they’ve managed to completely turn the place around in the 90’s. Once the de facto resting place for malcontents, people at the division admit, there’s only one person on restricted duty there today. Still, the earlier practices had consequences. Property Clerk officers were not able to hand over all the evidence originally stored in 1988 for the Christine Diefenbach case.

The people at the Property Clerk may have figured, what’s the point? The chances of solving a cold case even as little as a few years after it happened are slim. Before DNA became a serious factor in clearing cases, they must have really believed there was no point in holding onto evidence. Few detectives came back for anything from these older cases. Plus, there are storage issues. There have been over 70,000 murders in the past 100 years (not to mention all the other crimes). Where can they possibly keep all that evidence?

When someone is murdered in New York, the first thing a detective does with the evidence is go to the precinct to see the Property Officer, who will give the detective vouchers with serial numbers for each piece or group of evidence. The voucher lists each object and describes it as either investigatory (needs tests), property (needs to be stored), or arrest (will be needed for court). Belongings of the victim that do not require testing are left with the Property Officer. From there it will either go to the Property Clerk’s office in that borough, or to one of four large Property Clerk warehouses located around the city. Evidence for testing goes into envelopes (once it was discovered that bacteria grew inside plastic envelopes and caused DNA to degrade, the department switched to paper). Then it’s taken to either the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner or to the NYPD’s Forensic Investigations Division, more commonly referred to as the Police Lab, in Queens.

Once the tests at the OCME are complete, a report is sent to the detective and the evidence is put into what are alternately referred to as DNA, DOA (Dead On Arrival) or blood barrels. Every month, ten to fifteen DOA barrels are delivered directly to the Property Clerk’s warehouse in Queens. The people at the warehouse make sure that what the OCME says is in there is really in there, then they issue a transfer receipt for the OCME, give the barrel a number, log it and store it.

There is no statute of limitations on murder. Technically, any evidence from an unsolved murder should still be sitting in warehouses around the city. Given the approximately 23,000 plus unsolved homicides in New York, there should be more than a century’s worth of evidence disintegrating, unremembered, in a storeroom somewhere.

Unclaimed property is assigned a value and sold online at an eBay-like company called Property Bureau. Cars are the exception–they are still auctioned off from the warehouse in Queens. Before Property Bureau, all auctions were held at the Queens warehouse.

Drugs, and money being held as evidence have been disappearing from the Property Clerk offices since the beginning. A 1952 report by the Institute of Public Administration is just one of many calling for the installation of controls and audits on the office of the Property Clerk. Their own annual reports indicated that they understood the need for a better system of record keeping and security. The biggest heist of all, and the one that led to the greatest reforms, was the theft of $10 million dollars worth of heroin from the second floor at 400 Broome Street annex. The heroin came from the famous 1962 French Connection case. Although the drugs were discovered missing in 1970, the police department suspected it was taken earlier. They hadn’t kept tabs on what they had in a while, and what started out as 24 pounds unaccounted for climbed to 398 pounds following a crash inventory.

This led to enormous changes within the Property Clerk Division. However, the new controls that were effectively applied to drugs and money were not applied to evidence from homicides until the 1990’s. No one was trying to walk off with old bloodstained shirts. They weren’t particularly interested in saving them either. If Tommy Wray [a cold case detective] needs old evidence for further examination or testing or for an appearance in court, he has to get the storage numbers from the Property Clerk or the Police Lab, and then go down to the warehouses himself to get it. That’s when his problems begin.

First, was the evidence ever really stored there in the first place? A retired detective described what it was like at the Property Clerk’s in a 1972 New York Times article. “You can walk into that office and you have to wait with maybe 50 or 60 other guys in order to get to a little window and take out evidence or return it.” It wasn;t worth the trouble. If the evidence was important, they held onto it, he said. I recently stood with Steve Kaplan at the Property Clerk window in Manhattan and waited. Nothing has changed. We stood for two hours, unacknowledged. When I argued that we should complain Kaplan said, “Then we would wait forever.”

Next, even if the evidence was stored there, did the Property Clerk save it or throw it out? “I saw a guy in there with a pitchfork, throwing old evidence out into a dumpster,” one Cold Case detective remembers. It’s difficult to find evidence from cases earlier than 1990. “Whenever they can’t find something they always give one of the same three excuses,” one frustrated detective said. “The fire, flood or the move.” The people at the Property Clerk sometimes attribute the missing evidence to a fire at a large warehouse that used to be located under the Brooklyn Queens Expressway. A search of FDNY records turned up one minor fire, on November 2, 1990, which did ignite some boxes and clothing, and while some evidence was certainly lost, it wasn’t big enough to explain why there is almost no evidence prior to the 1980’s in the Property Clerk’s possession. Jean Sanseverino’s ring, her mother’s wedding ring, which her father picked up while stationed in Germany during WW1, and which was deposited with the Brooklyn Property Clerk in 1951, was either sold or thrown out long ago. There’s nothing from the fifties left there today. One vouchered handgun from a 1949 unsolved homicide case has survived, along with a few boxes containing a small number of homicide cases from the 1970’s.

The oldest DOA barrels remaining in the Property Clerk’s possession are from 1986, and they’re stored in the Erie Basin warehouse, which is primarily used to store cars. No one knows what’s in all of the older barrels. They were filled before anyone knew how to properly store these kinds of items and they’re not going to open them without guys in hazmat suits. “We opened a barrel one time and it was filled with maggots,” someone who worked there remembered. One detective said he’d find envelopes eaten through by rats. Another detective described the warehouses as :The bowels of hell. It was disgusting.”

The area around the warehouses is generally filled with light industry, auto body shops, scrap metal yards, recycling plants, transportation hubs. Inside, it’s damp, dank, like an unfinished basement, with concrete and dirt floors. Evidence used to be piled up around poles which were numbered, spray painted in red, readable today. Now it’s stored on metal shelves. People who work there use hand cream a lot because the powder and the latex from the gloves they use while working dries their skin. It rained recently and there were puddles and mud in the ground at one warehouse. “We’re dirty but we’re happy,” one person who worked there said. The warehouses look like that final shot of Raiders of the Lost Ark, when they are putting away the Ark of the Covenant, amongst endless stacks of wooden crates. Here, there are fifty foot tall towers of cardboard DOA barrels, with some showing signs of fluid damage. Each barrel holds 20 to 25 envelopes of evidence. There are roughly five or six thousand barrels. At 25 envelops per barrel, that could represent up to 150,000 crimes.

The inventory and storage operations at the warehouses are crude. They don’t use computers. They’ve got pens and logbooks and file cabinets. If there’s anything on a computer it’s because an individual who knows the software program Excel took it upon himself to put it there for his use alone. There’s no climate control at the warehouses. No air-filtering. A few half open barrels and boxes with torn paper envelopes exposing knives that presumably still might hold biological evidence sit on the shelves. Contamination seems like it would be an issue but Dr. Robert Shaler from the OCME argues, “You can’t deny the results. These are storehouses. You go into this old evidence, and even though it wasn’t handled in the best mechanism, you still get results which are valid. You have a blood stain, and it’s a big, huge juicy blood stain. Even though somebody may have handled that with their fingers forty years ago, there’s going to be so much less DNA from the person who handled it, than there is of the evidence. The evidence DNA is going to swamp out whatever contamination is there.”

“If the suspect’s DNA is there you still have to explain it. There has to be a reason for what you are seeing.”

Money is a big part of the storage problem. Computerization is not in the budget. There’s no more space to be had even though forty to fifty barrels come in every single month. The Property Clerk processed 29,000 vouchers in 1943. They’ve got 1.2 million now. Still, despite a lack of funds and decades of bad habits, in the 90’s, around the same time the police department got serious about DNA, the Property Clerk Division got their act together with respect to homicide evidence. The problems at the Property Clerk have been pronounced under control many times over the years, but DNA finally did it. Rape kits are refrigerated. Homicide evidence, particularly any serological evidence, is no longer thrown out. The newer barrels are inventoried, sealed and marked. Armed personnel and motion detectors are on every Property Clerk floor. Nothing leaves without a 49 from a commanding officer or a letter from an ADA or a subpoena. Different controls exist at each local borough office, but at the Brooklyn office for instance, only so many people can stand at the Property Clerk window at any one time. The rest must wait outside a locked door until they’re buzzed in and photographed. Before anything leaves any borough storeroom, the officer taking away the evidence will be fingerprinted, and those fingerprints are attached to the Property Clerk invoice.

Inspector Jack Trabitz, the commanding officer of the Property Clerk Division, claims they now have a 100% inventory, and they conduct unannounced spot checks to prove it. When I visited the warehouse, even though their inventory methods were not state of the art, they were still able to quickly say where everything was.

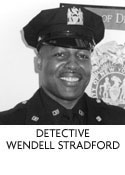

The people at the Property Clerk today are thorough and intent about their work, but many of the murders being investigated by the Cold Case detectives happened before these diligent officers got there. This might explain the attitude Cold Case detectives sometimes encounter when they show up looking for decades old evidence. When they request evidence from the 60’s, 70’s and 80’s, the people at the Property Clerk point out that those items were stored before their time, before they got things right. They don’t want to be held responsible, and, anticipating the traditionally low opinion many within the NYPD have of people at the Property Clerk, they sometimes go on the offensive. :Find it yourself,” the officer at the Property Clerk’s warehouse told Wendell Stradford and his partner Carl Harrison (aka Chuck), when they came looking for evidence from a 1988 case where a nine-year-old girl and her mother were raped and murdered. Harrison had just picked up the case and was trying to track down about a dozen Property Clerk vouchers. He called the Property Clerk two or three times a day for a month asking about them. They finally gave him some storage numbers and told him he’d have to find the rest himself. Chuck was most interested in a vaginal swab that had been taken from the little girl. According to a piece of paper in the case folder, there was a possibility that the vaginal swab was at a private DNA lab in Maryland called Cellmark Diagnostics. The people at Cellmark told Chuck that they had extracted DNA from the swab and sent it back to the Police Lab in small tubes. The Police Lab said they sent them back to Property Clerk. Chuck and Wendell went back to the Property Clerk and looked themselves. No tubes. They went through the Police Lab logs books for that week looking for a clue. Then they found the answer. The Lab was supposed to send the evidence back to the Bronx Property Clerk, but they gave the package a Manhattan storage number. It never got to the Bronx. Chuck and Wendell found the tubes sitting in a box at the Manhattan Property Clerk. They took them to the OCME and got a hit. They now have a new suspect.

Clearly, there are people at the Property Clerk who hate their job and are miserable, but they no longer define the division. The best detectives find out who the best PAAs are (Police Administrative Assistant, the people who actually look for evidence), the ones who know where everything is and won’t give up until they find it.

That’s the end of the section from my book, although I talk about the Property Clerk Division throughout the book. I wanted to mention two other places to find information, in addition to the the police precinct themselves.

Office of the Chief Medical Examiner

The ME’s office stores samples when they conduct serological tests, and they have a warehouse, too.

Central Records

The NYPD’s Central Records Division has a warehouse in Brooklyn where they store, among other things, 187 boxes full of case records for unsolved homicides spanning the years 1921 to 1973. Some boxes have a few cases, some have thirty or more. They may be falling apart from age, but there are probably 4,000 to 7,000 case files there.

Central Records stores other records, including crime scene photographs going back to 1948. Also at the Central Records warehouse’a few random stacks of old logbooks, and decades worth of fingerprint cards.

One Police Plaza

In the basement of 1PP, glass plate negatives from the early 1900’s sit in piles in a small caged room, cracking anytime someone steps too hard. There are also endless file cabinets full of film strips the NYPD has been making of the public, taken mostly at demonstrations, and going back for many decades

3 responses so far ↓

1 Cecilia // Jul 17, 2006 at 2:22 pm

Alan Newton, a Bronx man, was released from prison after serving 22 years for a rape he did not commit. His release came 12 years after he first made a motion for the results of DNA testing, which the police, as part of its routine criminal investigation, claimed had been lost. Only after a series of motions did the department locate the evidence Ñ in precisely the spot it was supposed to be.

http://nypdconfidential.com/

Mr. Newton would not have spent so much time in prison had the department did their job properly.

2 Stacy Horn // Jul 17, 2006 at 4:33 pm

I know! It was his story that prompted what I posted. I wonder how many other Alan Newtons are out there.

3 Cecilia // Jul 19, 2006 at 9:00 am

Well, there’s the story of Ronald Bower, in jail for rapes that were probably committed by someone else. There was a shirt with DNA on it that mysteriously disappeared from the property room.

It is a truly sad story and can easily be found by googling two names – Ronald Bower and Mike Perez. Amy Fisher did a good series on Bower for the Long Island Press.